Early this year, Shardul, Aalok and I visited India in overlapping windows (wow this rarely happens!) During that overlap, we finally realized our long-held dream of touristing in Kerala together!… just kidding >:( We decided to be ‘realistic’ and ‘sensible’ about it all and spent a week taking trains around southern Maharashtra :P

Our route was cobbled together pretty randomly1 at first…

…but in retrospect, OBVIOUSLY, there were underlying themes. These destinations all had a diversity of cultures — ethnic, linguistic & religious. This is partially due to the region’s proximity to current state borders2, and partially because for centuries, the Deccan has seen shifting alliances and changing regimes. Second, most of these towns contained pilgrimage sites honoring local deities or saints. Revered by locals across faiths, these figures often had an important presence in rural legend and tradition.

Aalok and Shardul are great at documenting their travels/adventures when they go out into the world. This time, the task is mine. Here goes!

Day 1: Gulbarga

We left Pune (home base for all three of us) at 06:00 on January 3, via the Pune-Secunderabad Shatabdi Express. Gulbarga3 is a (leisurely) growing, multi-cultural city close to the KA-MH border. In terms of historical significance, we found4 mostly forts/mausoleums relevant to the Bahmani sultanate, built in the 13th and 14th centuries. Bijapur, the former seat of the Adilshahi and home to the acoustic marvel of the Gol Ghumaz, is a more popular destination nearby and we were often asked why we didn’t go there instead.

I happen to have an aunt in Gulbarga, who hosted and fed us with a lot of love, and provided a base for us for the day. Shout out Soni fai <3 Her family also runs a fancyyy school there, of which we eventually got a tour.

We only spent the daytime in Gulbarga, so we had about four hours to visit four locations of interest. It was move move move. Excellent! We started at the temple of Sharanbasavesvara5. Devotees sang an aarti (rhythmic prayer) while automatic mechanical drums clanged contentedly to their own beat. Next, we walked around the sprawling ruins of the Gulbarga fort (that some locals had never heard of, in spite of it being a giant fortification right in the middle of the city) and passed by the 14th-century Jama Masjid in the heart of the fort (which, in contrast, everyone knew how to find).

Meandering through the town, which was casually bustling even in the hot ‘winter’ afternoon, we visited the Haft6 Ghumbaz and the neaby dargah / shrine of Sufi saint Khwaja Bande Nawaz. The large dargah complex attracts visitors across faiths from near and far. A struggling peace threaded itself through the groups of devotees, leaving behind a strong scent of rose and sandalwood. Finally, in the evening, we took a train to Solapur to spend the night. We stayed in the guest room of a farmhouse that also operates as a Catholic Home for children. The farmhouse was in the middle of nowhere, but we still heard truck drivers blasting party music all night as they carried goods out of a nearby sugarcane factory. Luckily, we had many train journeys, and naps, in our near future.

Day 2: Pandharpur

The next morning, we caught the Kalaburagi-Kolhapur SF Express to Pandharpur. Pandharpur is primarily a pilgrimage site. The otherwise sleepy town attracts around a million devotees during the annual waari foot pilgrimage. During waari, believers from all over Maharashtra walk to the Vitthal mandir (temple of Vitthal) in the center of this town. In addition to being a folk cultural phenomenon, the waari has a rich musical and poetic tradition, so we were all enthusiastic.

I visited Pandharpur about eight years ago for a high school athletics meet, and stopped by the temple. I remembered walking, alone, into a stone hall. The crowd of people at the gaabhara / sanctum blocked any chance of getting more than a quick glimpse of Vitthal, but I enjoyed the serenity (in other words — I was there for the vibes). Faith — the right word is shraddha — seeped out of the stone columns, as some weary farmers rested their backs there. With this sweet memory in mind, I suggested Pandharpur as one of our stops on this tour.

This time was different, though. The temple was so crowded, even though it was January and the waari season is not until July or August. To make things “efficient”, the temple organization had set up two lines to enter the temple. Each line snaked around the building, was ushered into the sanctum, and quickly yeeted straight back outside. Keep it moving, the security personnel inside reminded us. We offered our flowers on the first available surface. We only got a chance to sit down for a few minutes by slipping away from the line in the neighboring Rukmini mandir.

Our evening was quieter. Tucked into one of the small winding streets next to the Vitthal mandir is a Jain temple with barely any traffic. We stepped inside briefly, enjoying the silence. At night, we visited the Chandrabhaga river, a five minute walk from the temple. The river is revered as her own deity. All of us share an appreciation and respect for natural entities, and we felt a tug towards the river that could border on spiritual. Shardul took a moment to wade into the water, while Aalok and I enjoyed the stillness of the waterfront at night.

At the end though, ‘peace’ was earned with difficulty in Pandharpur. The lines between pilgrimage site and tourism industry blurred jarringly. The air was filled with tens of voices selling things — offerings, water bottles, toys, blessings, lodging, shoe storage, whatnot. I found it a bit overwhelming.

Luckily, the next day we retreated from civilization entirely. Leaving Pandharpur around 10:00, we got back on the Kalaburagi-Kolhapur SF express and rode all the way to Kolhapur. Reaching around 14:45, we took a pre-arranged cab to the quiet fort city of Panhala.

Day 3: Panhala

The forts of Panhala and nearby Vishalgad are famous in Maharashtra for the battle of Pawan Khind7, which enabled Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj to escape a siege and safely reach Vishalgad from Panhala.

Built in the 12th century, Panhala was first conquered by the Yadavs of Devgiri. It passed through the hands of the Bahamani sultanate, the Adilshahi / Bijapur sultanate, and finally the Maratha swaraj in the 17th century. The Adilshahi made significant modifications, adding a lot of the fortifications and buildings that are seen today. Although I squinted really hard, I could not read the Farsi calligraphy on the walls. It was, regrettably, a skill issue.

Panhala is sprinkled with the ruins of simple buildings such as wells, granaries, prayer halls, and lookout towers. Back in the day, this was a whole town. Unsurprisingly, it is still a whole town. Modern bungalows, small gardens, temples, and government buildings now coexist with the abandoned old ones. People go about their lives.

Panhala is a functional but laid-back village. Appropriately, our accommodation was a chill one-bedroom bungalow nestled on a forested road. It was better equipped than our previous stays, with even a functional kitchen. This lent itself to a night of joking around and fighting over the correct way to make Maggi (I was almost right). In the morning, we went out again to walk and skip around in the young sunlight. We found a (modern) radio broadcasting office and a few more (abandoned) lookout points.

Although it made our route a bit convoluted, putting Panhala on Day 3 was a great choice. The higher altitude and lower population density was a breath of fresh air.

Fun fact: our Panhala accommodation was right opposite the bungalow where veteran singer Lata Mangeshkar used to live. A few groups of people drove by just to look at the gates for a couple of minutes. Thus, our only destination without a religious site on the itinerary brought us to a pilgrimage spot of a different kind — a magnet for those rasik8 of Hindustani classical music! And how fitting, because Hindustani classical music was the theme of our next stop: Miraj.

Day 4: Miraj

The town of Miraj is about an hour away from Kolhapur. A (very loud & clattery) bus was easy enough to find. On the way, I scrolled through a tongue-in-cheek blog post that bemoaned the stereotype of Miraj as containing only ‘doctors9, dust, and donkeys.’ The author argued that the real allure of Miraj lies in its laid-back, multicultural society, the delightful linguistic quirks of the local dialect (“One may stipulate that Aurangzeb perished not of age, but after having heard the people of Miraj speak Urdu.”), and the yearly festivities that center around the dargah of Sufi saint Khwaja Shamsuddin Mirasaheb.

Critically, Miraj is a center for instrument crafting — particularly the sitar and tanpura — and the latter is indispensable for any Hindustani classical vocalist. Shardul and Aalok both grew up learning Hindustani classical music, and I grew up with it always in the house due to my mom’s interest. Shardul, in fact, has been learning the sitar in Switzerland!

A single sitar takes days to make. The main resonating chamber of the instrument is literally a vegetable — a bhopala / gourd10 (Marathi). Once the gourds are dried out, they are sorted by size. An appropriately-sized gourd can be chosen for the desired pitch range of an instrument. This dried gourd is soaked in a chemical that gives it some flexibility and stretched out into the appropriate shape. Then, it is fitted with an ornate front plate and ‘neck’ carved out of red cedar wood11 and a long handle. Strings are made of German steel, and acoustically coupled with the resonating chamber via a hard bridge of bone or ebony. Finally, according to the taste of the musician and/or the crafter, designs and embellishments are added. As each sitar or tanpura is made individually, customization is common. A larger tanpura gourd may provide better accompaniment for deeper voices. A sitar player may need an instrument adapted to their playing style12.

We wanted to see all this magic up close. First, we went into a music shop that services and tunes all sorts of instruments. As we walked in, a white-haired man was fiddling with a harmonium under the curious eye of a customer. His son, in a corner, had taken one entirely apart. Bits and pieces lay on the floor. Guitars hung off the back walls. The Mirajkar13 family runs this store and seemed influential within the music scene of Miraj. The son, probably a few years older than us, had just finished a formal course in musical instrument creation specifically. He told us about their effort to modernize the process of sitarmaking in Miraj and gain government recognition for it. “One sitar takes a few days to make,” he explained. “If we had machines, which of course experienced craftspeople would tune, we could make a few sitars per day.”

The Mirajkar family directed us to a nearby workshop which actually crafts sitars — from the gourd to the finished product. This was run by the Sitarmaker14 family. We peeked into the bare storefront-shed where some men were shaping wood. The head of the household, observing from a chair outside, directed us into an inner workshop. There, one of his sons applied a final round of polish to almost-complete sitars. We chatted over some generously offered chaha :) This family had a different perspective on the future of sitar-making. “Even carving wood to the perfect thickness relies entirely on the intuition of the craftsman,” one of them said, dismissing the idea of mechanization. “You could use a machine, but the sound just won’t be the same.”

Who is right? Time will tell. It’s possible that mechanization will bring access to sitars (and to the tanpura) for people who want a lower-cost, one-size-fits-all option, while the traditional craftsmen will still have business from experienced musicians with individual preferences. Regardless of differences on this topic, the two families had much in common — they had been making or tuning instruments for multiple generations, they had adopted surnames that reflected their craft, and they maintained a deep appreciation and understanding of Hindustani classical music.

Even the other cultural magnet of Miraj — the dargah — plays wonderfully into the musical history. One of the earliest proponents of the Kirana gharana15, eminent vocalist Abdul-Karim Khan Saheb, became an ardent devotee of the dargah during his lifetime. Multiple residents narrated the story — Khan Saheb, suffering from an incurable plague, was advised as a last resort to visit the dargah of Mirasaheb and perform some service there. He traveled to Miraj, and for three nights he sat under a tree in the dargah compound while singing, in service of the saint. Soon after, he was cured, and his faith solidified so strongly that he maintained a wish his whole life to be buried in Miraj.

Khan Saheb’s wish was fulfilled, but his musical service to the dargah would last much longer than he would realize. To this day, part of the annual celebration around the death anniversary of Khwaja Meerasaheb is a three-night musical festival. Eminent singers and musicians from across India travel to Miraj to perform. As it is considered a service to the saint, they do not charge a fee for this performance, no matter how established they may be.

We stopped by the dargah in the evening. We asked to pay our respects, and so Shardul and Aalok were whisked away into the (men-only) inner hall. Meanwhile, I chilled in the courtyard — under the same sprawling tree where Khan Saheb once sang. I got a moment alone to feel the deep Emotions that were now surfacing after a few days away from the daily routine. The hazy night buzzed pleasantly with singing and calls to prayer (and, less pleasantly, with the occasional mosquito). Some children played hide-and-seek nearby, shouting to each other in a delightful mix of Hindi and Marathi16.

Our train out of Miraj was not till midnight, so we actually went back to the dargah after dinner and sat there for a couple of hours. It had quietened down and reminded me of any neighborhood temple complex on a festive evening — overdressed kids running around with their cousins, people chatting around the courtyard in small groups, a scent of smoky sandalwood.

Day 5: Jejuri

We conked out on the train, all quite tired. When we got off at 05:50, in the dark, at the small and unpopulated Jejuri station, I had a moment of doubt. All through this trip, I had been trying to make the safest, most sensible decisions. And yet, here we were, in the dark, a half hour’s walk from significant civilization, with no real plan. Aaaaa—

—but just as we stepped out of the station, we saw one (1) shared rickshaw waiting outside. The driver crammed us in together with at least seven other people, took the most unnecessarily flouncy U-turn I have ever experienced, and off we rattled, to be dropped off promptly at the base of the Jejuri gad17. Stone stairs led up to the temple of Khandoba/Khanderaya18 on top. The main traditional offering to Khanderaya is bhandara, or turmeric powder. It covers the floors and perfumes the air. Sonyachi Jejuri (golden Jejuri / Jejuri of gold) is what poets have called the fort, inspired by this carpet of bright yellow.

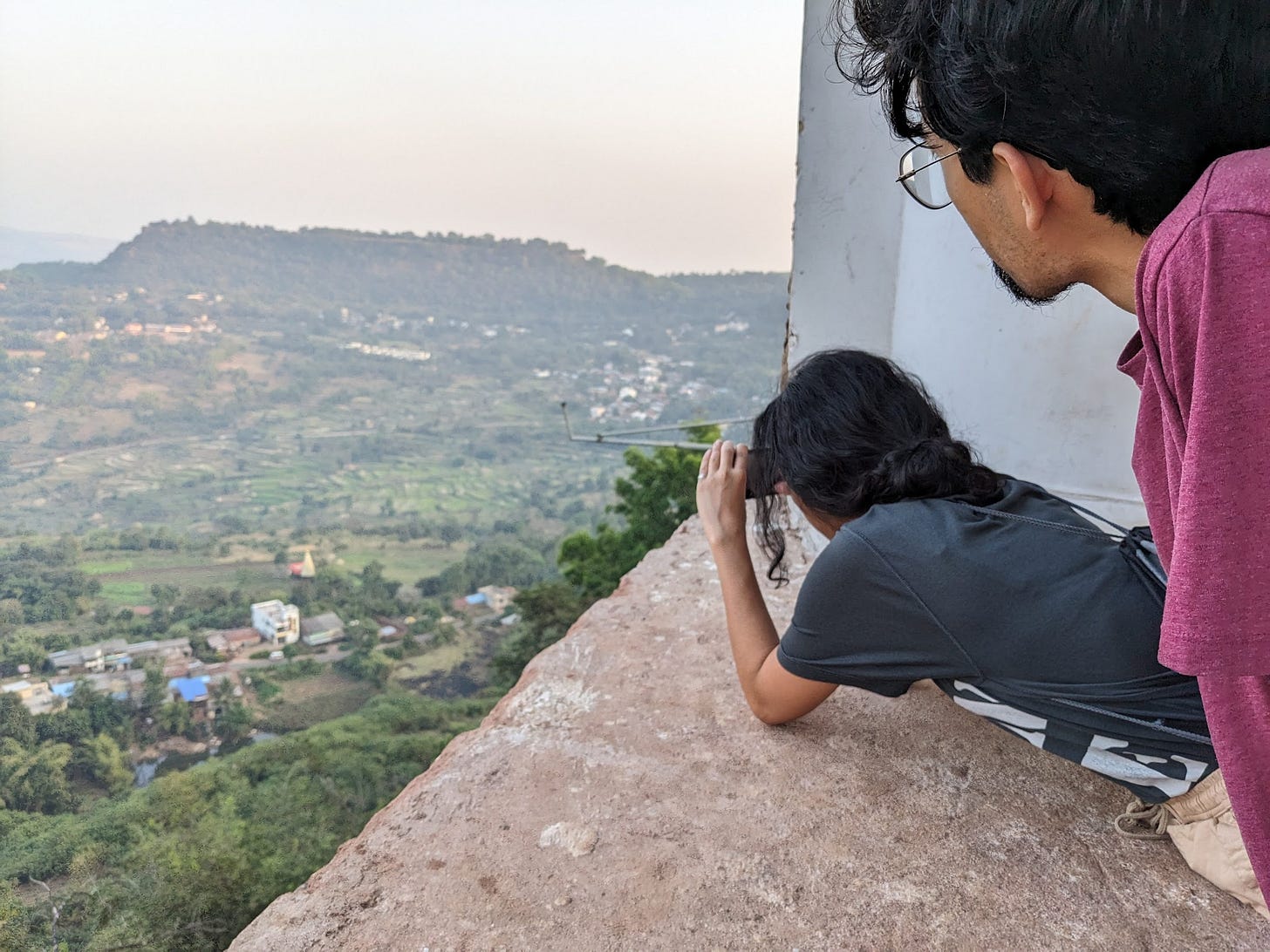

We made it up the stairs just in time for the first aarti of the morning at 06:45. After visiting the temple, we stayed to watch the sunrise from the hill. It was a warm and lovely start to the day. Khandoba is truly a folk deity. As we descended the hill, the crowds began to swell rapidly, including not just devotees but tourists and some school trips too. We found breakfast nearby, treated ourselves to the tiniest cup of cutting chai I have had the pleasure of holding (at least it was cute?), and caught a short bus back to Pune. That was the end!

Wrapping up

This was my first time planning a whole trip within India! One would think it would be easier — and some things were certainly more comfortable, like finding vegetarian food and casual social interactions — but after all, I have been living mostly in the US since leaving home. The systems are different. And I have recently gotten so used to being on my own (that could be a whole separate post), being in charge of my own schedule and plans, that sometimes it is hard to adjust to the whims and unexpected stressors of group travel. Even until literally the day of the trip, I was afraid I would be a boring ball of stress.

But that didn’t happen! And doing it with my close friends was a solid part of that. They know me well enough to anticipate what I like, and if they push me, they know how to do it right. And, as they are both responsible and organized (but still chill enough for spontaneity and fun), I could turn my brain off from time to time and trust the process. 10/10.

In sum, a nice week to look back on. I feel excited and confident about doing this more often! Kerala, anyone?

A different friend taught me the Marathi idiom ‘हिंग चड्डी पुस्तक तलवार’ (which I will not attempt to translate) to describe how (un)related our chosen destinations were to each other.

Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Telangana.

Also called Kalaburagi. Locals used ‘Gulbarga’, and in my head it has a more convincing etymology (gul / flower barga / garden), of which ‘Kalaburagi’ seems like a derivation. It may also simply be a linguistic difference, with Kalaburagi being the preferred form in Kannada? We colloquially used Gulbarga (we spoke Marathi or Hindi), so I have kept to that here.

‘Found’ is used because we did not look this up ahead of time :P

An 18th century saint revered by the Lingayat sect.

Meaning ‘seven’, seen for instance in hafta / week (Urdu) which is of course related to hept- (as in heptathlon) or sept- (as in September, at one point the seventh month), which is seen for example in Sanskrit-derived saptah / week (Hindi). Funnily (and quite unrelatedly), the Marathi word for week, athavda, contains a root for ‘eight’, not ‘seven’.

paawan / sacred khind / pass (Marathi). It was renamed in honor of the Maratha soldiers who were martyred there during the Adilshahi’s recapture of the fort. The Adilshahi army, led by Siddi Jauhar, laid relentless siege to Panhala. After months of siege, Shivaji Maharaj decided to escape. He headed to Vishalgad under the cover of night and rain, but Siddi Jauhar soon gave pursuit. A small group of Maratha soldiers, led by Baji Prabhu Deshpande, faced Siddi Jauhar’s much larger army in a doomed battle, to block them as long as possible in a mountain pass (khind). After this battle, Panhala was captured by Siddi Jauhar’s army. The Marathas recaptured it more than a decade later.

rasik / connoseiursersre how do you spell that word??

Miraj is home to many medical colleges, and as a result, many doctors set up practices there.

Coincidentally, one of the main sites of farming these gourds is Pandharpur!

laal / red deodar / cedar (Marathi) is what I remember, but it may actually have a different English name. Perhaps it refers to Toona ciliata, which is a type of mahogany.

Plenty of specifics were discussed, names of styles and famous instrumentalists were dropped, technical musical jargon was liberally used… and I regret to inform you that it all went over my head. Follow up with Shardul or Aalok if that’s interesting.

Literally, ‘resident of Miraj’/‘person from Miraj’.

Occupational surname in action!

School of art, in this case, music. ghar / home (Hindi/Urdu/Marathi). The kirana gharana was the school of music that taught many of the greatest classical Hindustani vocalists from the Maharashtra and Karnataka region, such as Pt. Bhimsen Joshi, or my mother’s favorite, Prabha Atre.

I do have friends and family who unabashedly mix these languages, but this was a new style of combination. I love sociolinguistics!

gad / fort (Marathi). I think in this context, it simply refers to the temple complex on a hill. There isn’t significant fortification. However, Khanderaya is said to have ruled over the land from here, hence it is still referred to as his fort.

Interchangeable. -ba / ‘paternal figure’ -raya / ‘king’ highlight two different aspects of the god — both a provider and a protector.